A long-term historical analysis of the Italian economy since 1815

During the period that followed its political unification, Italy has left the “periphery” of the world economy and managed to attain levels of income per capita similar to those of the industrialized countries of the Western world.

The aim of Lost Highway is to carry-out an original long-term historical analysis of the Italian economy since 1815 in order to reassess major structural shortcomings of the development processes.

The roots of the current economic malaise

However, since the early 1990s, this catching-up process seems to have been suddenly halted: in the last two decades, the average annual growth rate of Italian GDP (0.5%) has been less than a third (1.8%) of the average for rates of the four largest countries of the European Union (France, Germany, United Kingdom and Spain).

The economic record of the last decade is even bleaker with a negative growth rate (-0.6%), while the average of the other four countries is close to 1%.

These results cast doubts on the actual solidity of Italy’s standing among the advanced countries of the world economy.

In other words, is Italy still firmly placed among the group of most developed countries and is only facing a temporary crisis or, on the contrary, is gradually returning to the marginal position it had in the

centuries preceding the unification?

Relatedly, is the Italian decline of the last 20 years an only outcome of Italian difficulties to adapt to an increasing globalization of the world economy or should we look for deeper determinants in the history of its development process?

Interpretative framework

Our interpretative framework assumes that factor endowments (land, capital and human capital) determined the patterns of innovation and choice of technologies and thus the feasible rate of technical progress.

A key implication of this framework is that successful transfer of technologies from leaders to followers is positive correlated to the congruence of factor endowments, provided that the follower had the “right” social capabilities (Abramovitz 1986).

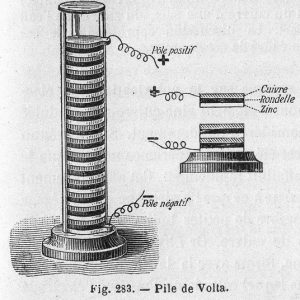

From this point of view, XIX and early XX century Italy was at a clear disadvantage. It was not short of some brilliant inventors (such as Guglielmo Marconi, Antonio Meucci and Alessandro Volta), but its factor endowment differed substantially from that of leading industrial countries.

In fact, it had abundant unskilled labour, scarce land, low human capital and no coal. This context has determined the emergence of a relatively labour-intensive, capital- and skill-saving development trajectory that has shaped trade patterns, innovative activities and thus the historical dynamics of productivity.